Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: They all laughed at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round they all laughed when Edison recorded sound they all laughed at Wilbur and his brother when they said that man could fly they told Marconi wireless was a phony it's the same old cry.

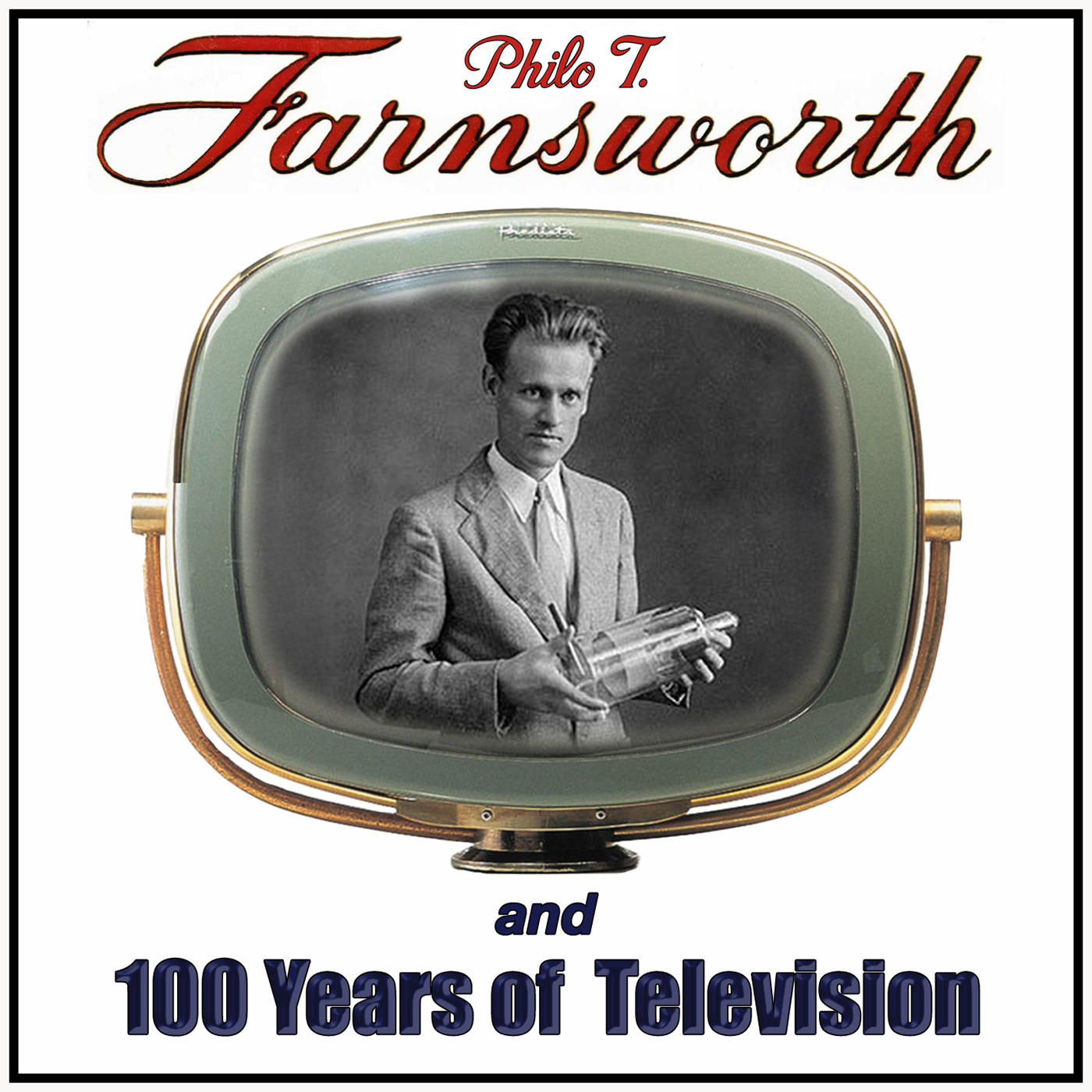

[00:00:21] Speaker B: Welcome to 100 Years of Television. This is episode number seven, Black Light Machine.

For 100 weeks starting in October 2025, this podcast is going to recall the top 100 milestones in the first 100 years of television and video.

We're going to look back at the technological innovations that spawned the medium, the programs that demonstrated its awesome potential, and explore the cultural changes that have emerged and in the century since its invention.

The countdown is pegged to culminate on September 7, 2027. That's the 100th anniversary of the day that television as we know it was invented.

I'm Paul Schatzkin, author of the Boy who Invented Television, the definitive biography of Philo T. Farnsworth, who invented the world's first all electronic television system.

In the last episode, after several weeks recounting the prehistory of television prior to 1927, we finally got around to September 7, 1927, the pivotal date we seek to celebrate. Today we'll look back at some of the things that were happening even as that momentous date approached and passed.

In 1927, radio was still a relatively young medium, but the subject of television was already generating headlines, among them this one in the New York Times on April 8, 1927, far off speakers seen as well as heard in a test of television.

The headline was accompanied by a photo of then Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover holding a telephone receiver to his ear and gazing into a box.

The previous day at&T President Walter Gifford sat at a terminal in New York city and essentially FaceTimed with Hoover, who was sitting at a similar terminal in Washington, D.C.

the system they used has to be considered the prize winner for the most bizarre mechanical television system ever devised.

Developed by Dr. Herbert Ives at the recently formed Bell Labs, the transmitting end of the system used the familiar scanning disk that had been the heart of television experiments since Paul Nipkoff first proposed it in 1884.

But photos of the receiver show an electric motor rigged to an ungainly harness of 2,500 pairs of individual wires.

Each of those wires sent an electrical impulse to a matrix of 50 rows of 50 individual bulbs in a two foot by two foot display.

The resulting demonstration only rendered 50 blurry lines per frame, but was heralded in the Times as a triumph.

Herbert Hoover made a speech in Washington yesterday, the Page One article began, and the audience in New York both heard and saw him.

And while a subhead was careful to note that the system's commercial use was in doubt, some sense of the new medium's eventual future was foreshadowed in other parts of the demonstration.

Secretary Hoover's remarks were followed by a vaudeville comedian who told jokes with an Irish brogue and then smeared on blackface to continue with a new line of quips in Negro dialect.

Something like the AT&T demonstration was replicated across the Atlantic the following year.

Of all the names associated with television before 1927, perhaps none is more prominent than that of John Logie Baird.

Ask anybody in Britain who invented television and they'll cite Baird as readily as they recall Shakespeare or Churchill.

Baird was a somewhat eccentric Scotsman who tinkered with a string of oddball inventions in the 1920s. A rust resistant glass razor jam made with paraffin wax, and most famously, Baird's thermal socks, electrically heated footwear meant to keep feet warm in England's perpetually damp climate.

None of these ventures amounted to much, but they did emerge from an approach to invention that was equal parts ingenuity, determination and quirk.

By 1923, Baird's string of curiosities left him pining for worthier pursuits.

From his boarding house in Hastings, he directed his efforts toward the rising interest in transmitting moving pictures by electrical means.

Starting with a homemade nipkoff disc, a T chest cabinet, bicycle lamps, darning needles and scavenged radio parts, Baird began assembling the contraption he called the Televisor.

The results were primitive, ghostly images of the disembodied head of a ventriloquist dummy called Stooky Bill.

But they were results.

In 1925, Baird hauled his contraption to Selfridge's department store in London for what was widely reported as the first demonstration of television and the reason the Brits still think he invented it.

On February 9, 1928, Baird's acclaim went global when another headline in the New York Times reported from Hartsdale, New York, that persons in Britain seen here by television as they pose before Baird's electronic eye.

The article reported that a man and a woman sat before an electric eye in a London laboratory tonight, and a group of persons in a darkened cellar in this village outside of New York watched them turn their heads and move from side to side.

That stellar account is recalled as the first transatlantic transmission of television.

It cannot be stressed enough that all the publicity surrounding events prior to and even after 1927 employed archaic systems based on the electromechanics of the 19th century, when clearly what was required was an approach that embodied the advances in physics that rose in the early 20th century. Relativity and quantum mechanics.

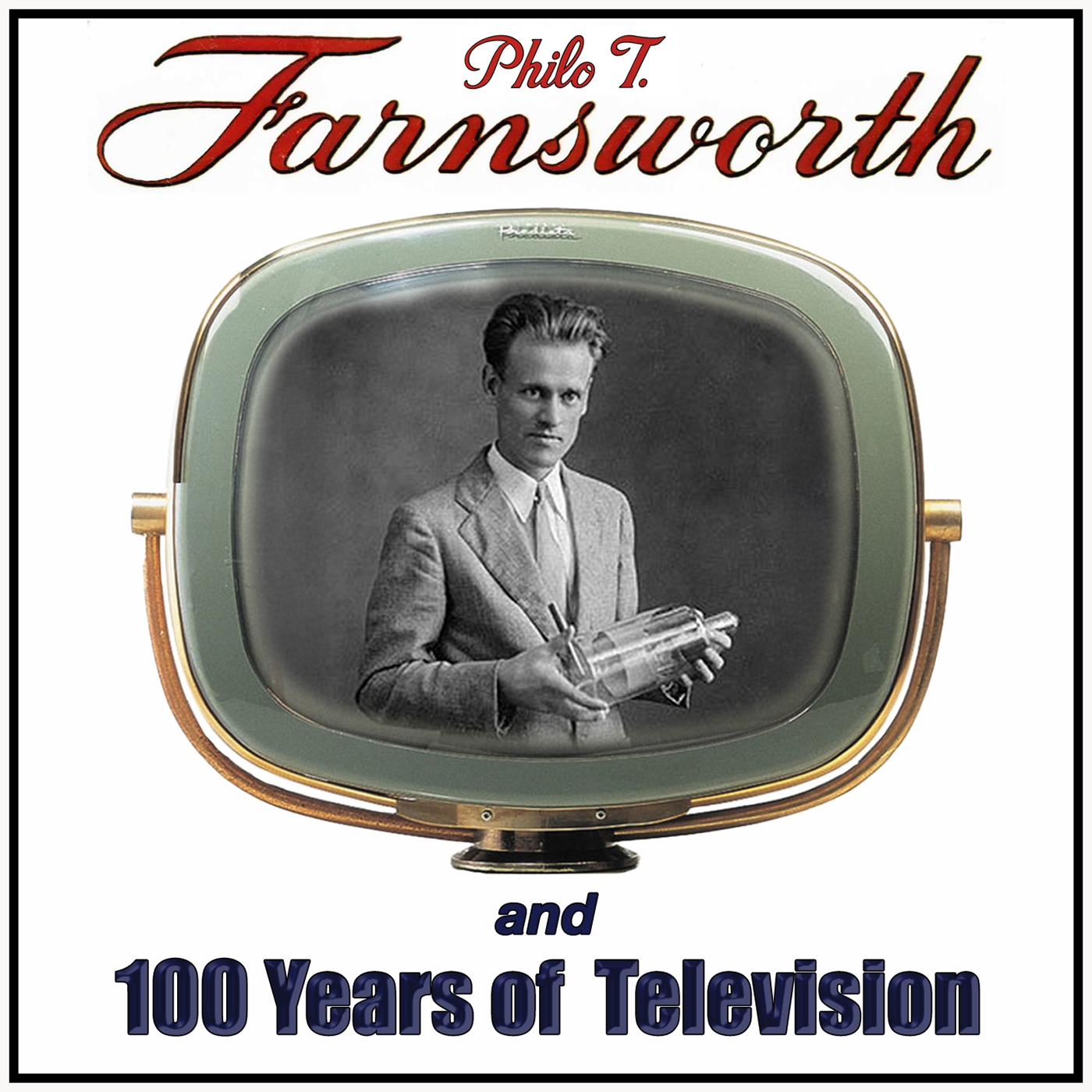

The news that one man had utilized that knowledge in the quest for television was revealed to the public in the pages of the San Francisco Chronicle on September 3, 1928, with a headline that read, S.F. mann's Invention to Revolutionize Television New Plan Bans Rotating Disc in Black Light.

A front page photo shows Philo T. Farnsworth, sporting a mustache he thought would make him look older than his 22 years, posing with the sending and receiving tubes for the television system he invented and reports.

Two major advances in television were announced yesterday in San Francisco.

Philo T. Farnsworth and local capitalists headed by W.W. crocker and Roy N. Bishop are financing the experiments and have aided him in obtaining basic patents on the system.

New Principle Applied all television systems now in use employ a revolving disk 2ft in diameter to break up or scan the image.

Farnsworth Systems employs no moving parts whatever. Instead of moving the machine, he varies the electric current that plays over the image and thus gets the necessary scanning perfect motion records.

His system is a queer looking little image in a bluish light now, one that frequently smudges and blurs. But the basic principle is achieved, and perfection is now a matter of engineering.

The sending tube is about the size of an ordinary quart jar that a housewife would use to preserve fruit.

Farnsworth had operated his small laboratory at 202 Green street in San Francisco in relative secrecy for nearly two years.

The only visitors were friends, family and his financial backers who wanted to cash in on their investment from the moment its minimal viability was achieved.

When the press was finally admitted less than a year after the principle was proven, it was at the insistence of those investors hoping to raise more money or to sell out to a bigger company.

But that's not what Farnsworth wanted.

Unlike his investors, Farnsworth fully understood the long term value in the portfolio of patents he'd begun to assemble. He rightfully expected that the royalties from those patents would be paid by all the companies that those investors wanted to sell out to.

Farnsworth's interest was less in the potential fortune that his invention might generate than than it was for the freedom that fortune could afford him to pursue whatever line of invention he chose to pursue in the future.

Farnsworth thought he was living the 20th century version of the American dream that the likes of Morse, Edison, Bell, and Marconi had realized in their time, he may have neglected to take into account the vested interests that those accomplished predecessors had left behind, even though the threshold from mechanical to electronic video had finally been crossed. It was clear, as one backer said after first seeing what Farnsworth had wrought, that it would take a mountain of money as high as Telegraph Hill to monetize the crude tubes Farnsworth posed for in the Chronicle photos.

Farnsworth, his wife Pem, her brother Cliff, and his bride Lola, picked up a copy of the Chronicle from a newsstand on March Market Street.

After momentarily basking in the glow of their sudden renown, Phil struck a more sober tone for what lay in store for them.

This leaves us wide open to our competition, phil reflected, though containing his genuine apprehensions. We're still years ahead of the pack, but with our limited financing, we'll be working under a severe handicap.

Then, trying to sound more optimistic, he expressed precisely what distinguished their operation.

We have something the big companies don't have.

Our small size allows us to maneuver like a speedboat alongside their juggernauts. But even speedboats eventually run out of gas.

We have our work cut out for us, that's for sure.

Indeed, once that article appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle and went out on the wire services across the country, all those big companies on the east coast, not least among them the ambitious and well capitalized Radio Corporation of America, now knew that real television existed in the world, and the race was on to deliver it to the marketplace and reap the abundant rewards that were sure to follow.

Before we wrap up this episode, I've got one footnote to add.

I am compelled at times to use the word electronic to distinguish Philo Farnsworth's invention from the mechanical systems that preceded it. I do this largely to mollify other historians who take a broader view of this record and insist on the use of that qualifier. But who are we kidding? Once television went all electronic, it was the only kind that mattered.

This brings us to the end of episode seven. Stay tuned for the next episode Countdown 99, where the general public gets its first glimpse of what is in store when Farnsworth demonstrates his invention at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia in the summer of 1934.

Thanks for listening to 100 Years of Television and a two year countdown to the Centennial of Television on September 7, 2027.

For more, aim your gizmo to tv centennial.com this podcast was written, recorded, edited, engineered and uploaded by me, Paul Schatzkin, and is a production of Farnovision.com if television was invented by somebody named Farnsworth, why don't we call it Farnovision?

[00:13:25] Speaker A: They all said we never would be happy they laughed at us and how but ho ho ho you got to laugh at now.