Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: They all laughed at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round they all laughed when Edison recorded sound.

[00:00:10] Speaker B: They.

[00:00:11] Speaker A: All laughed at Wilbur and his brother when they said that man could fly they told Marconi wireless was a phony it's the same old cry.

[00:00:21] Speaker B: Welcome to 100 Years of Television.

This is Countdown Number 96.

Berlin, August 1936.

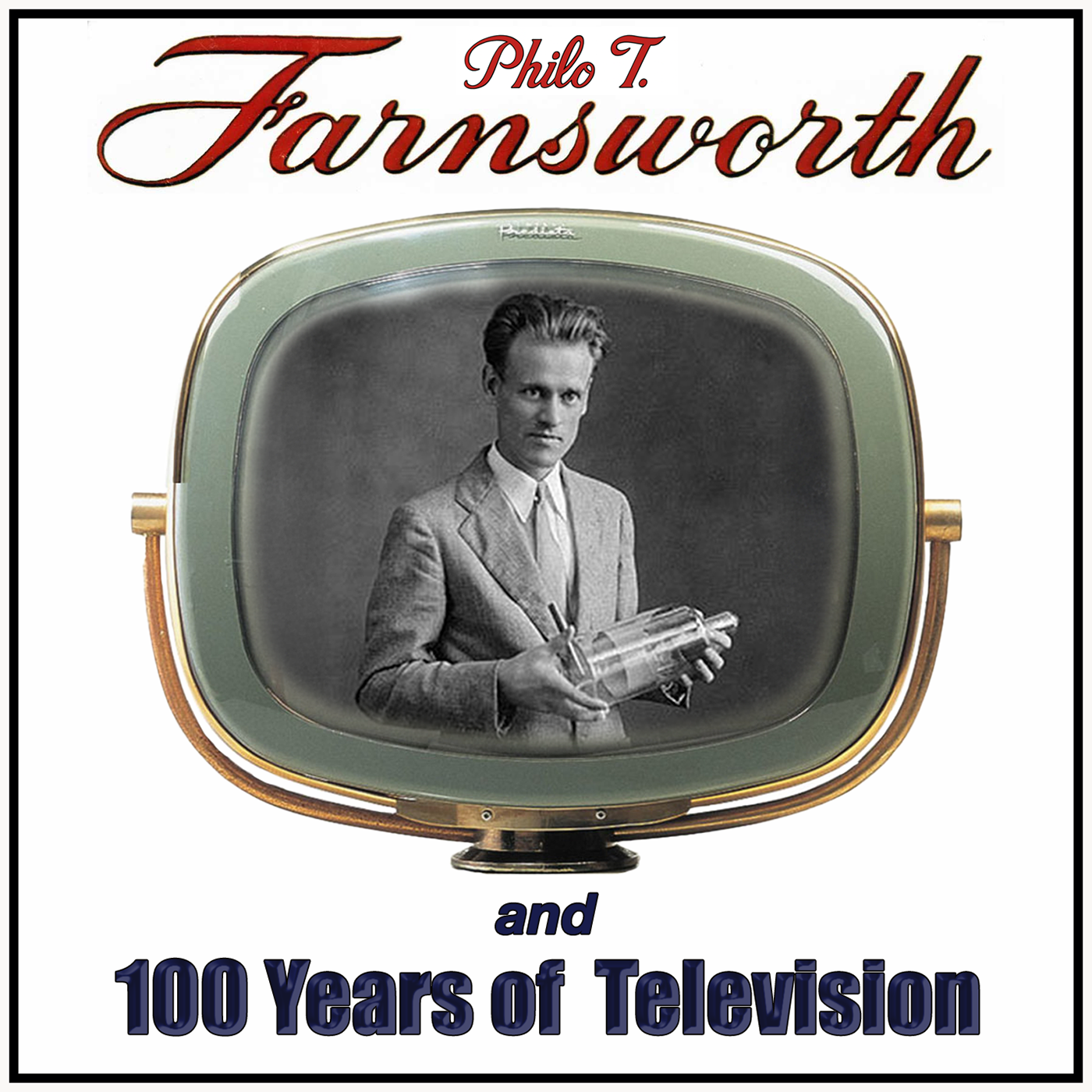

For 100 weeks that started in October 2025, this podcast is going to recall the top 100 milestones in the first 100 Years of Television and video. The countdown is pegged to culminate on September 7, 2027, the 100th anniversary of the day television was invented. Paul I'm Paul Shatzkin, author of the Boy who Invented Television, the definitive biography of Philo T. Farnsworth, who invented the world's first all electronic television system.

In the last episode, the United States Patent Office settled, if not exactly once and for all, who had invented electronic television.

Today, we begin to witness the practical use of television in international affairs.

In the summer of 1936, athletic spectacle, technical innovation and political propaganda all converged around the first international sporting event ever shown on television. The Olympic Games, staged for two weeks in Berlin, Germany.

All the major players in the global race for television were on the scene, including the man whose invention nearly 10 years earlier made the moment possible, Philo T. Farnsworth.

Germany's National Socialist Government, AKA the Nazis, was eager to showcase its technical superiority and invested heavily in preparations for the coverage.

A consortium of German companies called Fernsee Oktiengesselschaft, which translates literally to Television Joint Stock Company, pulled together the engineering expertise of Bosch, the optics of Zeiss Icon and the radio capabilities of Telefunken to build the necessary hardware.

Despite all the German expertise, the breakthrough that made the television broadcast possible came from abroad.

In 1934, Fernse secured a license from Philo T. Farnsworth for the use of his image dissector, the revolutionary camera tube at the heart of all electronic video.

For Farnsworth, the license provided some needed funding for his ongoing legal battle with rca.

For Fernsee, it gave German engineers the technology they needed to to accelerate their television development in time for the Games.

Of course, television receivers had yet to find their way into any German homes. So the regime built 25 public viewing halls known as television parlors in Berlin and Potsdam.

These venues, outfitted with projection screens and receivers, allowed audiences of 40 to 100 people to watch the Games in rotating shifts.

The Fernsee led consortium employed a hybrid system utilizing both film and live video.

In some cases, Olympic events were recorded on film, quickly developed and then transmitted through film chains that employed the Farnsworth image dissector. While not as immediate as the live transmissions, the hybrid system worked well enough to impress visiting dignitaries and engineers from around the world, among them Philo Farnsworth and his wife Pem, who were in Berlin after a brief stint in London helping out John Logie Baird.

As a guest of Fernsee, the Farnsworths witnessed firsthand how his invention was used not in American living rooms, but in the heart of Nazi Germany.

We can only imagine the surreal experience of seeing television showcased under a curtain of Nazi banners.

While back in the USA the RC of A was still denying Farnsworth had anything to do with inventing it from the site in Berlin, only select games were televised, including track and field, boxing, rowing and gymnastics.

The broadcasts were transmitted via VHF and received via closed circuit transmission only in the official parlors. But for the first time, a relatively large audience could witness live sports from a distance, a feat previously unimaginable.

The 1936 Olympic broadcast was as much propaganda as it was progress.

It was designed to project an image of German supremacy in both sport and science.

But behind the scenes, the televising was powered by an American innovation and personally witnessed by the inventor whose own country had yet to fully recognize or or benefit from his work.

Over the two week span of the Olympics, more than 150,000 viewers tuned in as Jesse Owens, a black man from America, won the gold medal in four prestigious track events.

History has long since noted the irony of this African American track star dismantling the myth of Aryan supremacy that Hitler's games were meant to establish.

And all the drama unfolded through the cameras in viewing halls that were themselves based on an American invention.

The legacy was immediate and far reaching.

Within a year, the BBC launched its first regular television service, inspired in part by what they'd witnessed in Berlin. And just three years later, NBC followed suit in the United States.

The world was ready to see what television could do and television was ready to show it.

This brings us to the end of number 96 in the countdown of the top 100 milestones in the first 100 years of television.

Stay tuned for the next episode where the British Broadcasting Corporation, the venerable BBC, launches the world's first regular television programming service.

Thanks for listening to 100 Years of Television, a two year countdown to the centennial of television on September 7, 2027.

For more, just aim your gizmo to 100yearstv.com this podcast was written, recorded, edited, engineered and uploaded by me, Paul Schatzkin and is a production of Farnovision.com if television was invented by somebody named Farnsworth, why don't we call it Farnovision?

[00:07:26] Speaker A: They all said we never would be happy. They laughed at us and ha.

But ho ho ho, who got the laughs at now?