Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: They all laughed at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round.

They all laughed when Edison recorded sound.

They all laughed at Wilbur and his brother when they said that man could fly.

They told Marconi wireless was a phony. It's the same old cry.

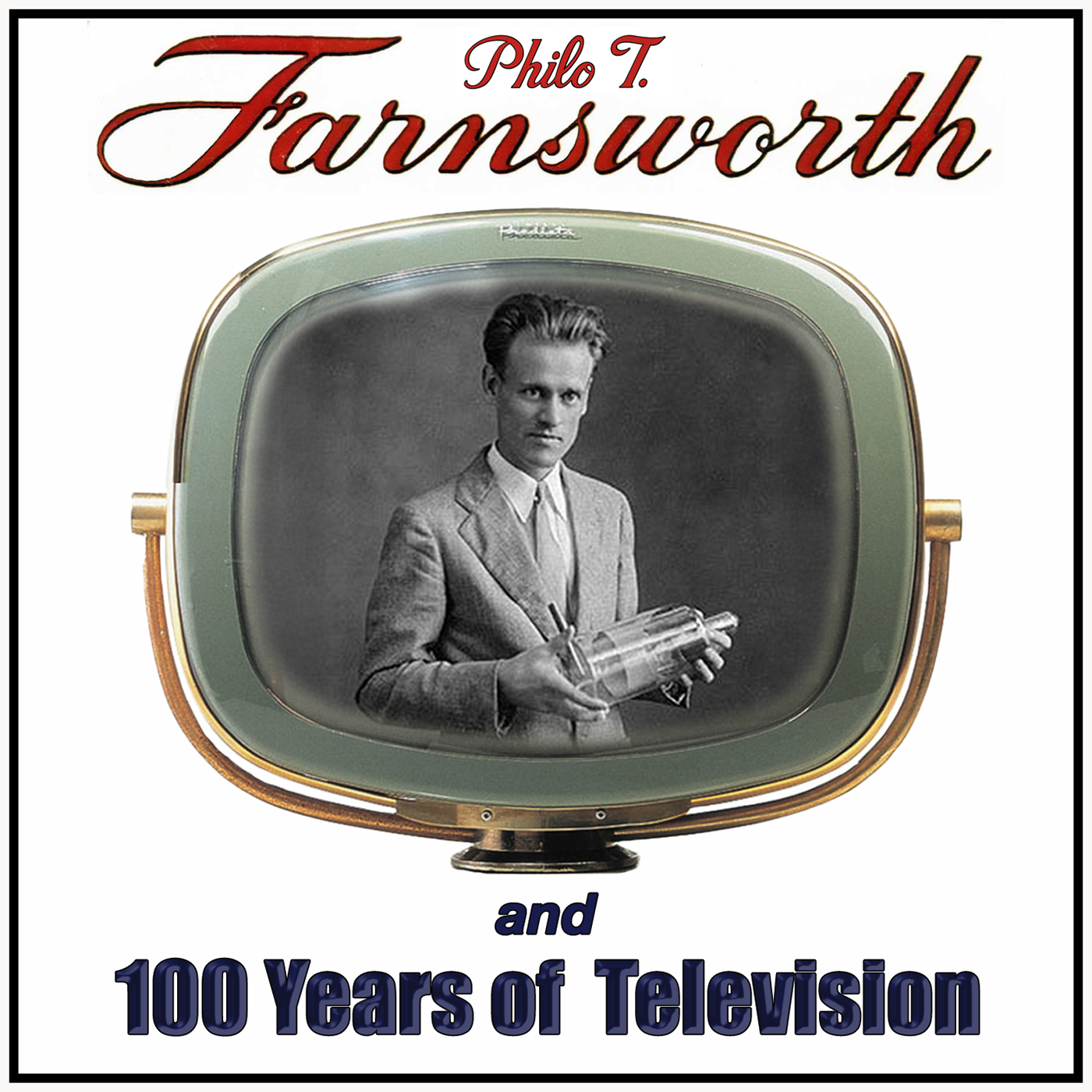

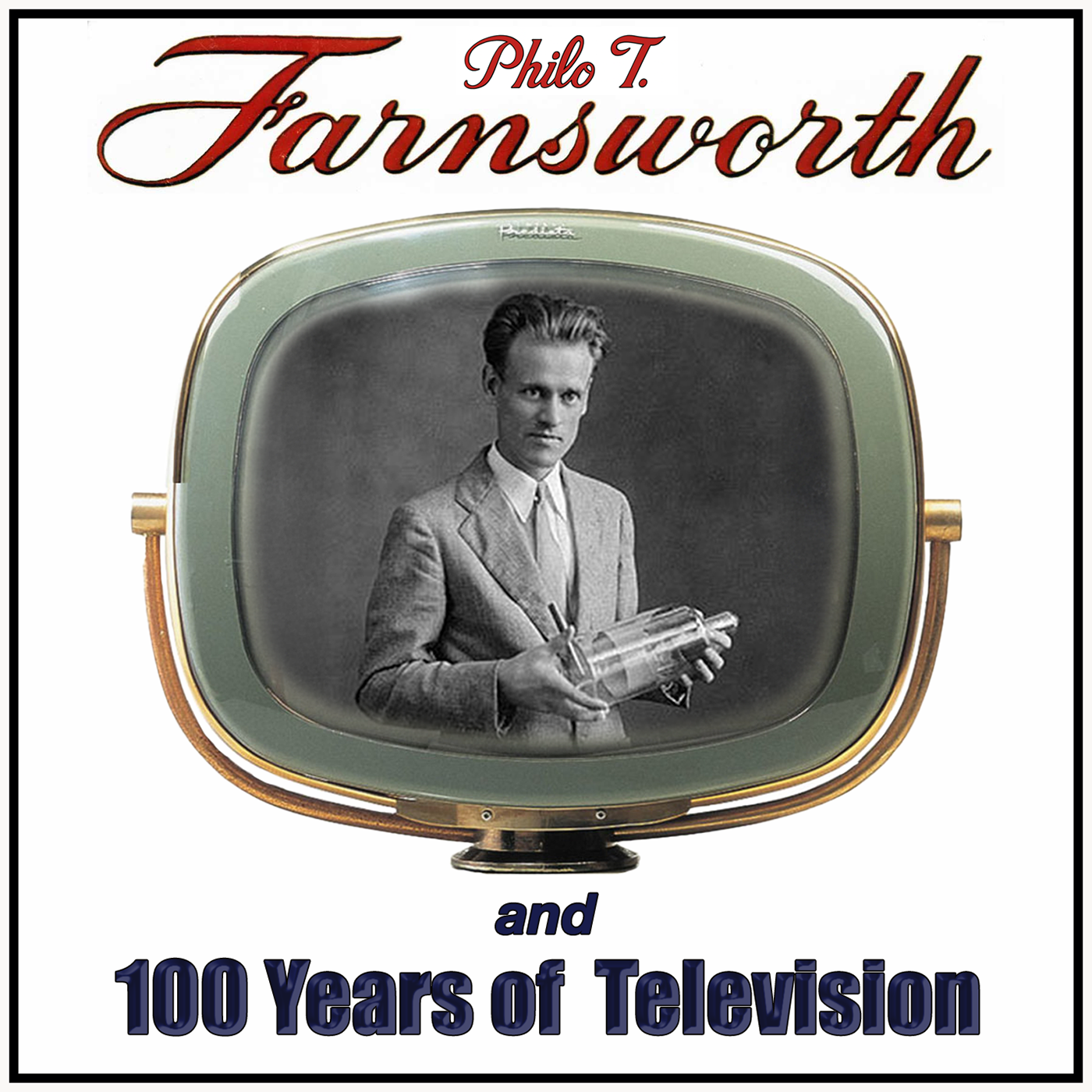

[00:00:20] Speaker B: Welcome to 100 Years of Television.

This is episode number 13, countdown number 94.

Now we add sight to sound for 100 weeks that started in October 2025.

This podcast is going to recall the top 100 milestones in the first 100 years of television and video.

The countdown is pegged to culminate on September 7, 2027, the 100th anniversary of the day when television as we know it was invented.

I'm Paul Schatzkin, author of the Boy who Invented Television, the definitive biography of Philo T. Farnsworth, who invented the world's first all electronic television system.

In the last episode we saw the orderly manner in which regular television service was introduced in Britain in 1936.

In this episode we'll see how the Radio Corporation of America tried to duplicate what Britain had done in the United States three years later.

If David Sarnoff can be recalled for any single ambition, it is his desire to be remembered as the man who single handedly delivered television unto the world.

By 1939, David Sarnoff was the president of the Radio Corporation of America, the world's largest manufacturer of radios and phonographs, and the parent company of NBC, America's largest radio network.

Over more than a decade, starting in the late 1920s, Sarnoff had spent an estimated $10 million of RCA's profits. That's roughly 240 million in $2025 on television research.

Much of that money was spent developing an in house alternative to Philo Farnsworth's patents with Vladimir Zwerkin's iconoscope. The rest was spent on litigation to invalidate or commandeer Farnsworth's patents.

By 1939, RCA's board of directors was starting to question when they might see some sort of payoff from all that investment of time and treasure.

The iconoscope of the 1930s worked about as well as Farnsworth's image dissector.

Both tubes required prodigious amounts of light to produce a usable picture.

The iconoscope was built around a radically different configuration from the image dissector, owing in part to the imperative of circumventing Farnsworth. But the iconoscope was such a quirky bit of gear that one RCA engineer expressed his frustration with it by saying, getting a decent picture out of an iconoscope took a miracle a sweat towel and a stiff drink afterward.

Meanwhile, Farnsworth had won all but a very few minor cases in his ongoing litigation with RCA.

By 1939, Farnsworth and his tiny lab gang had compiled a portfolio of more than 100 US and foreign patents that covered all the essentials of electronic video scanning, synchronization, electron beam deflection, and the novel but indispensable sawtooth wave.

On top of the patent office's 1935 decision covered in Countdown, no. 97, Priority of Invention, this collection of patents made Farnsworth's grip in the new art of television all but impenetrable.

But that was not the sort of thing that could stop David Sarnoff.

All of this uncertainty around the technology meant that the industry could not even discuss the kinds of standards that would be necessary for an orderly introduction of the new medium.

Nevertheless, Sarnoff informed his board of directors that he was going to launch commercial television, and he had the perfect venue in mind the 1939 New York World's Fair.

The fair opened to the General Public on April 30, 1939. Sarnoff opened the RCA Pavilion in front of an iconoscope camera.

Now we add sight to sound, sarnoff proclaimed broadly declaring the arrival of a new art so important in its implication that it is bound to affect all society.

At least he was right about that much, if premature by nearly a decade, Sarnoff's proclamation was followed by a brief address by Franklin Roosevelt, the first appearance on television by a sitting US president.

What RCA's cranky iconoscope could not reveal that day was that the Federal Communications Commission had yet to grant anybody permission to engage in any kind of commercial television broadcasting.

Only a few hundred people saw the inaugural broadcast, Transmitted live by RCA's Experimental Station, W2XBS in Manhattan to a few hundred receivers scattered around the fairgrounds and selected venues in and around New York City.

For the moment, Sarnoff's gesture was strictly symbolic. As noted, there were still no national television signal standards, and there were fewer than 1,000 TV receivers, most of them owned by RCA or department stores.

The sparse programming RCA offered in the months that followed was still strictly experimental, cobbled together from news summaries, sporting events, and vaudeville acts.

The true nature of the World's Fair event was spelled out in the May 1939 edition of Fortune magazine with a headline that called the Future of television a 13 million dollar. If most of that gamble was attributed to the Fortune that Sarnoff had spent on television technology and litigation over the previous decade.

In contrast, Fortune estimated Farnsworth's expenditures at something in the neighborhood of just $1 million.

Such is the difference between actually inventing something and trying to engineer and litigate around it.

Unfortunately, the Fortune article also helped shape much of the public's early grasp of television's origin story. By introducing at least two lingering myths in its first paragraph, the article says that long after the World's Fair has become one of Grandfather's stories, April 30th will still be the day when they formally started television service in the U.S.

in fact, the occasion only signaled the beginning of a new phase of experimentation, one in which the public was invited to participate so long as they could pony up between $200 and $600, which would be 5,000 to 13,000 in $2025 for a 5 inch to 12 inch television set.

Then, in one of its most enduring misstatements, Fortune asserts television is not an invention at all, but the product of thousands of often unrelated experiments pieced together with the painstaking care of a paleontologist assembling the brittle, calcified shards of a dinosaur's skull.

And so begins the false construct that television was too complex to have been invented by any single individual. While it is true that television in the late 1930s was the culmination of a broad and costly engineering effort, Fortune conveniently ignores Farnsworth's profound, singular breakthrough, the one invention that made everything that followed possible, including and especially the so called launch at the New York World's Fair in the spring of 1939.

That event was very much unlike what had transpired in Britain three years earlier.

There, trials were conducted, technologies were evaluated and selected, and only then did the government agencies authorized to do so permit the BBC to begin regularly scheduled television broadcasting.

The comparison makes Sarnoff's World's Fair gambit seem all the more desperate.

That Fortune article does, however, offer the first hint of what was soon to come.

After years of contentious litigation, the article speculates that a cross licensing agreement between RCA and Farnsworth is imminent.

Indeed, a few months after the Fortune article appeared, RCA accepted the first license in its corporate history that required the company to pay royalties for the use of an outside inventor's patents to the tune of at least $1 million it would pay over time to Philo T. Farnsworth. Legend has it that RCA's attorney had tears in his eyes as he signed the agreement.

But that was in late September 1939, just a couple of weeks after Hitler's invasion of Poland, the real advent of television in America would have to wait until after World War II.

This brings us to the end of number 94 in the countdown of the top 100 milestones in the first 100 years of television.

Stay tuned for the next episode, where television's national pastime makes its television premiere later in 1939.

Thanks for listening to 100 Years of Television, a two year countdown to the centennial of television on September 7, 2027.

For more, aim your gizmo to onehundredyearstv.com where this installment's web post includes some tasty footnotes that question Vladimir's work and claim to have pioneered the storage principle that differentiates his iconoscope from Farnsworth's image to sector.

This podcast was written, recorded, edited, engineered and uploaded by me, Paul Schatzkin, and is a production of Farnovision.com if television was invented by somebody named Farnsworth, why don't we call it Farnovision?

[00:11:08] Speaker A: They all said we never would be happy they laughed at us and ha.

But how, how how we got the laughs right now.