Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: They all laughed at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round they all laughed when Edison recorded sound.

[00:00:10] Speaker B: They.

[00:00:11] Speaker A: All laughed at Wilbur and his brother when they said that man could fly they told Marconi wireless was a phony it's the same old cry.

[00:00:21] Speaker B: Welcome to 100 Years of Television.

This is episode number 14 countdown number 93 play ball for 100 weeks that started in October 2025. This podcast is going to recall the top 100 milestones in the first 100 years of television and video.

The countdown is pegged to culminate on September 7, 2027, the 100th anniversary of the day television as we know it was invented.

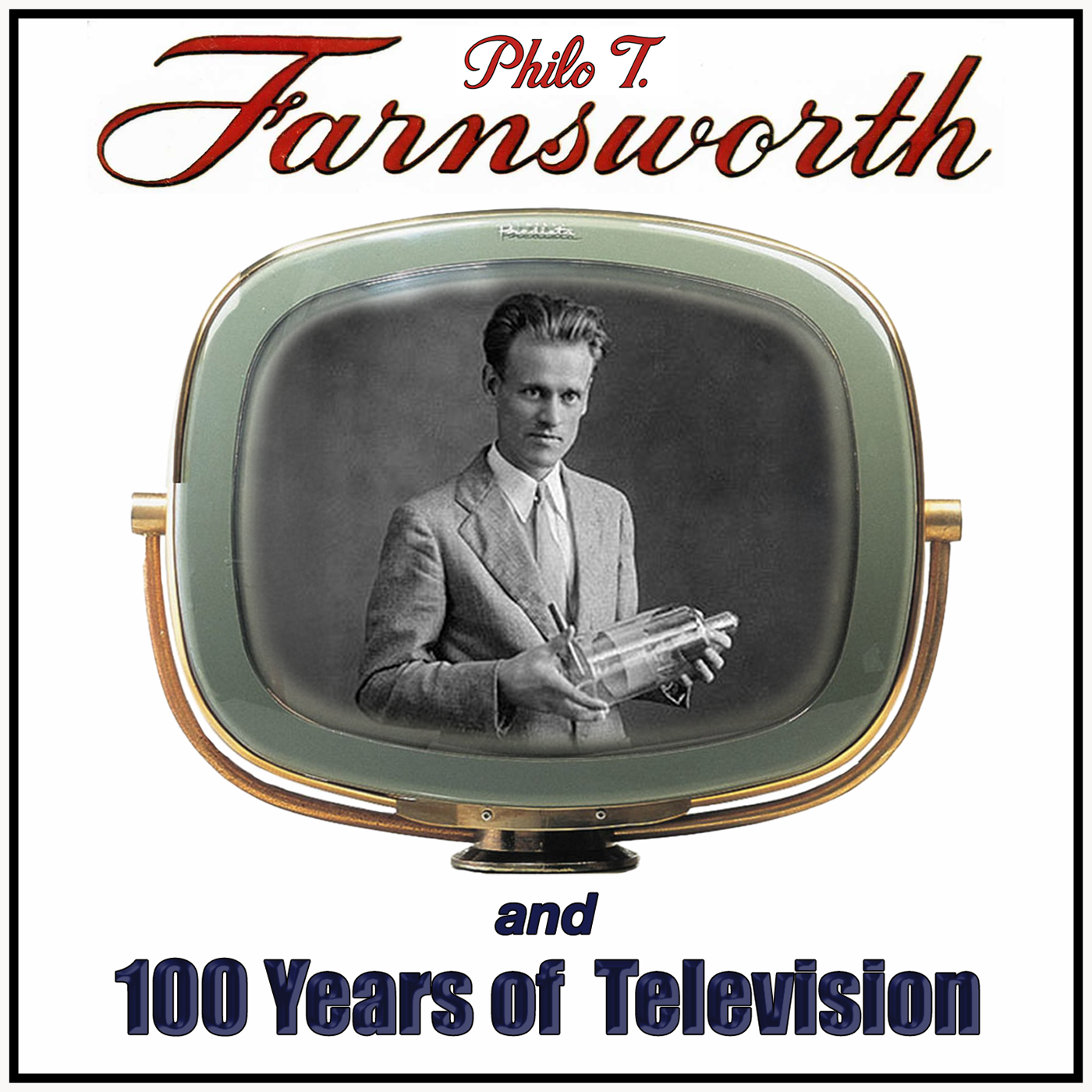

I'm Paul Schatzkin, author of the Boy who Invented Television, the definitive biography of Philo T. Farnsworth, who invented the world's first all electronic television system.

In the last episode, RCA made a premature splash with the introduction of television service at the New York World's Fair in the spring of 1939.

Today, television's experimental phase in America continues with the addition of professional sports to the programming repertoire.

The enduring relationship between television and professional sports in America began on August 26, 1939, when RCA and NBC broadcast the first televised Major League Baseball games, a double header between the Cincinnati Reds and the Dodgers at Brooklyn's Ebbets Field.

However, the Reds at Dodgers games were not the very first sports event broadcast on American television.

That distinction goes to a college game between the Columbia Lions and the Princeton Tigers on May 17, 1939, shortly after the unveiling of television service at the New York World's Fair. That was in Countdown 94. Now we add sight to sound.

RCA showed their new fangled medium to Bob Harron, the sports information director at Columbia University, who posed the obvious question, did you ever think of doing a sporting event?

About two weeks later, RCA set up cameras at Columbia's Bakers Field to broadcast the second half of a Columbia Princeton doubleheader, with sportscaster Bill Stern calling the action.

The telecast received considerable media coverage, including stories in the New York Times and Life magazine reporting on Columbia's 2 to 1 loss to Princeton in a 10 inning game.

Satisfied with the results from the Columbia experiment, RCA and NBC pitched the Brooklyn Dodgers about televising home games from Evetts Field.

The double header between the Reds and the Dodgers was transmitted on RCA's Experimental Station W2XM from an antenna atop Manhattan's Empire State Building.

Anyone within a roughly 50 mile radius of New York could watch the games, provided they were among the few hundred People fortunate enough to own or have a neighbor who owned a tv.

The games were covered by two cameras. One was fixed on the upper deck behind the batter's box, providing a view of the entire field.

The other was stationed behind the visiting team's dugout along the first baseline, covering the action around home plate.

Once a ball was put in play, the feed switched from a close up of the plate to a wide angle from the upper deck.

Those video images were supplied by RCA's Temperamental Iconoscope.

Bright, sunlit portions of the field contrasted with creeping afternoon shadows, which video engineers struggled to balance.

Still, viewers could see the batter swing, the fielders in motion, and even an occasional, if fuzzy, glimpse of the ball itself. The box store for the historic game reads like a comedy of errors, most of them performed on the field by the hapless Brooklyn Dodgers walked in runs, dropped pop flies, wild pitches and passed balls at the plate.

The final score was Cincinnati 5, Brooklyn 2.

The Dodgers recovered in the second game, outscoring the Reds 61 to split the doubleheader.

Play by play commentary was provided by Red Barber, already a well known voice in radio, who brought his legendary Southern drawl to the new medium.

Between the two games of the doubleheader, Barber kept the broadcast going with interviews in the stands and the press box.

Of course, there was no instant replay or fancy graphics, but this embryonic broadcast was enough to demonstrate how television could bring the national pastime straight into the nation's living rooms.

The timing of the milestone is also significant.

These games were played just a few months after RCA's widely publicized TV launch at the New York World's Fair and less than a week before Hitler's invasion of Poland and the start of World War II.

The war postponed the widespread adoption of television for another six years, but this first Major League Baseball broadcast established a template for what would eventually become one of television's most enduring staples.

From ebbets field in 1939 to global satellite broadcasts decades later, television and baseball grew together.

Those flickering images added a new visual dimension to the sport's golden age. In the 1950s and 60s, television changed the way fans saw the game.

And over the ensuing decades, the revenue generated from television would reshape the economics of not only baseball, but all of America's major sports.

This brings us to the end of number 93 in the countdown of the top 100 milestones in the first 100 years of television.

Stay tuned for the next episode when signal standards are finally adopted so that television broadcasting can begin in earnest in the country where it was actually invented.

Thanks for listening to 100 Years of Television, a two year countdown to the centennial of television on September 7, 2027.

For more, aim your gizmo to 100yearstv.com this podcast was written, recorded, edited, engineered and uploaded by me, Paul Schatzkin and is a production of Farnovision.com if television was invented by somebody named Farnsworth, then why don't we call it Farnovision?

[00:07:20] Speaker A: They all said we never would be happy. They laughed at us and ha.

But ho ho ho, who got the laughs right now?